Introduction

Extending upon the work of Shannon and Weaver, George Gerbner theorised a General Model of Communication in 1956 with additional elements like external reality and perception. This addition gave it more dynamic appeal than the latter model, as the message is not just a pre-existing entity but a product of external reality. The real world and its perception form a particular lens of a man or machine.

However, the model remains linear and process-based like its predecessors, where one thing occurs after another. Furthermore, the model sees the communication process occurring on two alternating dimensions and adds the perceptual or receptive, and the means and control dimension.

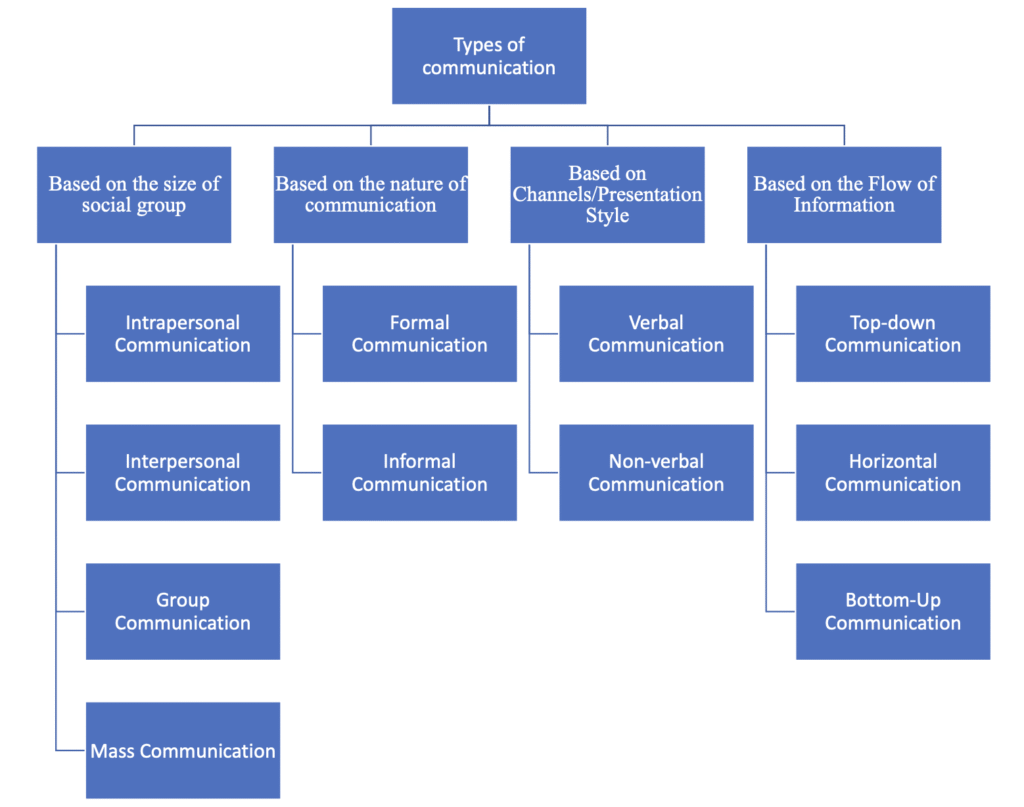

At first glance, the model seems to be way more complex than the other linear or process-based models. But in reality, the model is very easy to interpret and understand. Gerbner aimed to create it as a ‘general-purpose’ model applicable to all forms of communication, from interpersonal to mass communication.

Before we delve into the nuances of the model and try to understand each of its elements, it is crucial to take a step back and first take a peek into its creator’s life, which would help us build a more holistic overview of the model.

Background Information

George Gerbner, born in Budapest, Hungary, is one of the early and most influential communication scholars. He graduated in literature and anthropology. Gerbner escaped Hungary to avoid conscription into Nazi-allied Forces and entered the United States in 1942. He enrolled in the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) to study psychology and sociology, later transferring to UC Berkeley to study journalism. Upon graduating, he worked for several newspapers in various positions from copyboy to editor.

Later, Gerbner joined the US military and fought against Nazi forces, receiving the Bronze Star for his service. Post-World War II, after working as a writer and publicist for a few left parties, he started teaching journalism and went to the University of Southern California (USC) to conduct his master’s and doctorate degree in communication. His dissertation work, “Towards a General Model of Communication,” won the award for the best dissertation at USC.

In 1968, Gerbner headed the Cultural Indication Project (CIP) to document trends in television viewing and programming. The project, Gerbner’s most valuable contribution to the field of journalism, held a database of 3,000 television programs and 35,000 characters, contributing to the creation of Cultivation Theory and the concept of the mean world syndrome.

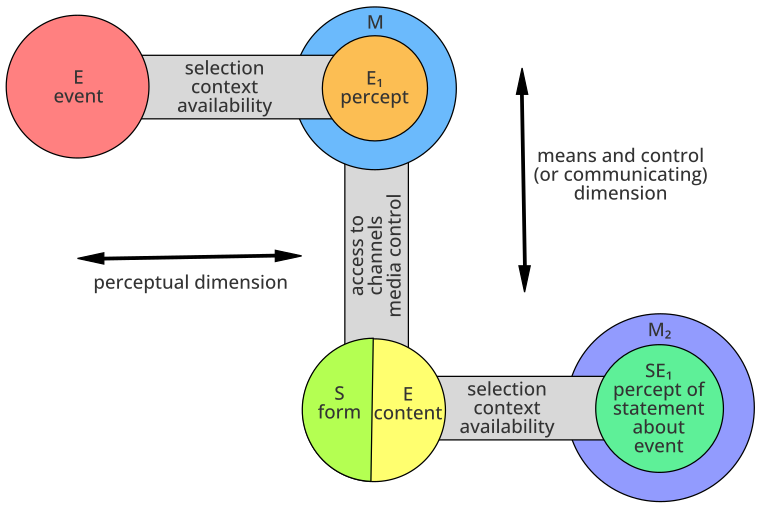

Gerbner sees the communication process consisting of two alternating dimensions:

- Perceptual or receptive or horizontal dimension: Corresponds to the relation between communicator and event.

- Means and Control or Communicating or vertical dimension: Corresponds to the relation between communicator and message.

Perceptual Dimension

The process of communication begins with an event or E that occurs in the real world. Meanwhile, a Man or Machine, labeled as M, perceives the event and creates his/her own perception of the event known as percept E1.

The relationship between the Event (E) and the event’s percept (E1) by a man or machine involves selection because a man or machine cannot capture the entire incident as it is. If M is a machine, selection depends upon its engineering or physical capabilities. For instance, a microphone will have different selection capabilities and limitations than a video camera.

If M is a man, the selection becomes more complex. Human perception is not a simple reception of stimuli; it is an outcome of continuous interaction and negotiation. Here we, as humans, try to match the external stimuli (event) with our internal thoughts and concepts (values and knowledge). Thus, when the interaction and negotiation are settled, meaning is assigned to that event, and perception is formed based upon those meanings.

Let’s try to understand it with an example from an imaginary world. Imagine an orthodox reporter (M) who has traditional values and is non-liberal or narrow-minded. He went to cover a hipster-rock concert (E) where people are wearing short clothes, colored hair, bold tattoos, publicly displaying affection, intoxicating, and listening to loud unsettling music.

The reporter’s initial reaction would be unsettling, and he’ll try to derive meaning from it based upon his pre-existing mental concepts. Thus, as an orthodox person, he would assume people going to these concerts are immoral, blatant, and rogue (selection). Based upon these meanings attached to behavior or attire, the reporter creates a negative percept (E1) of the events.

Or simply imagine an interpersonal scenario: you go to watch a cricket match alone and then later try to tell your friends about your experience of the game. Obviously, you won’t be able to give a ball-to-ball commentary on the game. You would nitpick the moments that intrigued you the most, like boundaries or turning points of the match, and the experience of watching the match live in the stadium with other people.

Thus, your (M), E1, or event’s perception is being conveyed. Another person supporting the opposition would have a completely different story to tell. This very attribute of the model relates it to reality.

As you can easily infer, the selection and conversion of E to E1, in the man’s case, is immensely dependent upon their culture, internal concepts, or thought patterns developed as a result of their cultural or life experience (Fiske, 1982, p. 26). Furthermore, when ‘M’ attempts to communicate its perception (E1), we enter the vertical or media and control dimension.

Media and Control Dimension

The whole idea of the vertical or the communicating or means control dimension is built upon the base of humans’ need/urge to share their experience and communication. Based upon the ‘availability and accessibility,’ the man converts his perception into ‘SE’ or what we normally call a message. S here stands for a signal or form which the message takes, like written, visual, oral, electronic, and E refers to its content, the core idea.

An important thing to note here is that the event is never perceived entirely. Similarly, when encoding the message, changing E1 to SE, it also loses some percept; usually, it’s too complex to be fully communicated.

Furthermore, E or the content can take different forms and can be communicated in a number of different ways. There are many potential S’s or signals to choose from, like an audio podcast, videos on YouTube, or a simple text on WhatsApp. It is crucial for communicators to choose the best possible form/signal/S for their content/E so the message could be communicated effectively.

The relation between form/signal/S and E/content is dynamic and interactive. Rather than looking at them as two different entities, Gerbner suggested looking at them as a unified concept where the chosen form will affect the content being conveyed. For example, the content (E) of a sports game will be different in face-to-face conversation (S) than in a newspaper (S), radio (S), television (S), and the internet (S).

I. A. Richards says content is not simply conveyed by the form. He labels it as the ‘vulgar packaging theory of communication,’ arguing that content is created during encoding when it takes a form. Before that, there is only drive or the need for encoding.

Selection plays a crucial role in the vertical dimension as well. First, there is the selection of ‘means’ or the medium or the channel of communication. Then there is selection within Percept E1. As we discussed earlier, the percept cannot be delivered in its entirety. Selection and distortion must occur during encoding. Moreover, another important element of the vertical dimension is access.

The Concept of Access

Access to the medium is a means of exerting power and social control. Two great examples of this statement come to life in Gerbner’s own experiences. The Nazis were able to capitalize on the early persuasive effects of mass media to turn people against the Jewish population. On the other hand, America and allied forces made use of mass media to instill a sense of national pride in their people and fight against the evils of the Nazis.

However, it is also true in interpersonal communication: authoritarian personalities or teachers will attempt to control others’ channels of communication, much like a totalitarian regime. For instance, the patriarch of the family may decide upon which news channels (E1) to watch, to what extent other members of the family are allowed to differ from his ideology (E1), and what events could be discussed.

The whole debate on democracy and free speech, where people have the right to express their views according to their will and lenses, has been at the center of debate for decades now. With the emergence of new media, a whole new dynamic of access has emerged because people now, so-called, have access to mass media through the internet.

Third Stage or Perceptual Dimension (Repetition)

For the third stage of the process, we revert back to the perceptual dimension or horizontal dimension. But here, of course, what is being perceived by the receiver, M2, is not an event or E, but a signal or statement about the event, or SE. Imagine you watching TV, reading a newspaper, listening to a friend’s hiking experience, or hearing a radio program.

It’s important to keep in mind that the whole process of stage one repeats itself. Even if you are watching television, you won’t simply accept or reject the whole message. Once again, there would be a negotiation between you and your mind which will help create your perception (E2).

Taking the concert example, as a rock music lover and open-minded person, you have been to concerts before and find the behavior of people completely normal because you see it as an expression of their individual personality. So, when you see coverage by the orthodox reporter, you won’t be able to relate and could end up thinking the reporter is inaccurate.

Now, when you (M2), in this case, try to share your precept (E2) about the E1, we once again enter the vertical dimension where you choose a medium like Twitter to share your perception, and it goes on. There could be simply as infinite M’s and E’s.

Advantages of the Model

- A general-purpose model: Gerbner’s model is a one-size-fits-all model which is not only applicable to mass communication but also equally applicable to interpersonal channels.

- Realises the message as part of cultural interaction: Unlike other process-based models, Gerbner’s model of communication does not treat the message as a preexisting entity. It realizes that the message is a product of interaction and negotiation between a man and their environment.

- Emphasises the significance of encoding: As mentioned in the latter point, the message is the product of interaction. Gerbner tells us it takes shape when the percept is converted into a signal or medium, and based upon the chosen medium, the content of the message would be decided to best convey the percept.

- Talks about access and control: Gerbner indicates that people who have direct control could possibly decide what percept is being conveyed and somewhat have power over the perception of other people.

- Emphasises on selection and context: Gerbner says people, based upon their orientation, upbringing, and ideas of the world or rules specified by their media organization (news values), select the most suitable bits of the event.

Criticism

- Linear model of communication: Although Gerbner mentions the dynamic nature of the message, he fails to realize the dynamic nature of the whole process of communication where one thing doesn’t occur after the other (arguably). Countless events take place simultaneously, and perceptions keep being formed and modified, often when people switch from one form of communication to another.

- Complex model of communication: At first glance, the model may seem confusing and complex to many new scholars, as there are many moving parts occurring at the same time, which might be hard to grasp. However, I personally find the whole idea of the model quite interesting rather than complex. Difference in perception! Well, we live in a democracy.

Conclusion In conclusion, George Gerbner’s Model of Communication provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the intricate dynamics involved in the communication process. By incorporating elements such as perceptual dimensions, media and control dimensions, and emphasizing the role of selection, encoding, and access, Gerbner’s model offers valuable insights into how messages are created, conveyed, and interpreted in various contexts. While the model has its advantages in providing a holistic view of communication, it also faces criticism for its linear approach and perceived complexity. Nonetheless, Gerbner’s contributions continue to shape our understanding of communication theory, highlighting the complex interplay between individuals, media, and society.

References:

- Fiske, J. (1982). Introduction to Communication Studies. Routledge.

- Gerbner, G. (1956). Toward a General Model of Communication. Audio-Visual Communication Review.

- McQuail, D., & Windahl, S. (2015). Communication Models for the Study of Mass Communications. Routledge.

- Richards, I. A. (1929). Practical Criticism: A Study of Literary Judgment. Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Severin, W. J., & Tankard, J. W. (2001). Communication Theories: Origins, Methods, and Uses in the Mass Media. Longman.